Soon after I discovered Waldorf education, I had a conversation with a friend whose daughter, like my son, was approaching kindergarten age. We lived in Los Angeles, where getting one’s child into the “right” kindergarten had as much significance as getting accepted to Harvard or Yale.

“Have you considered the Waldorf school?” I asked her.

“Oh, we looked at it, but ruled it out because they don’t believe in books. We are a family of readers,” she emphasized.

I was taken aback. Did my friend think that my husband I, both college graduates, didn’t value books or reading?

I knew that reading wasn’t formally taught in a Waldorf kindergarten, and I’d heard that children created their own textbooks, but in all my research, I’d never heard that Waldorf schools were anti-books. I would soon learn that this was one of many common misconceptions about Waldorf education.

In the coming years, I not only enrolled my son in the Waldorf school, but I also enrolled myself in Waldorf teacher training and came to a deeper understanding of how reading is taught. I hope that the insights I’ve gained will help some of you who may be considering Waldorf education.

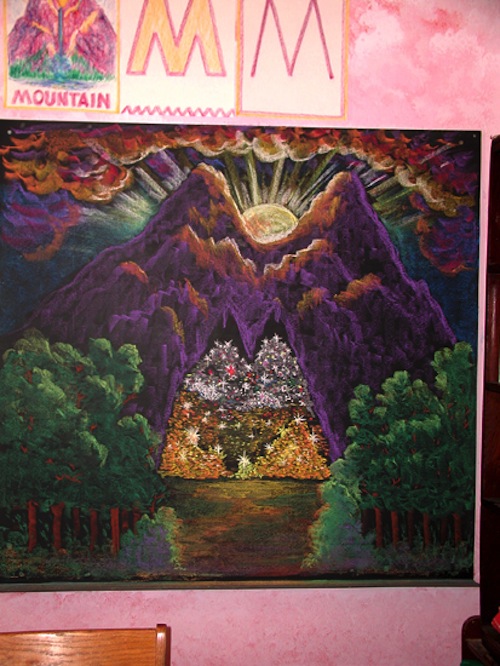

Blackboard Drawing by Allen Stovall

The Evolution of Language

In the evolution of humanity, spoken language developed first. Then came written language, originally through symbols (think hieroglyphics). Finally, once there was a written language, people learned to read.

This is exactly the sequence in which children master language, and so is the sequence in which reading is taught in Waldorf education. From birth to age seven, the focus is on the spoken word.

The children hear stories – nursery rhymes, nature stories, folktales and fairy tales. Teachers are careful to use the original language of fairy tales without “dumbing them down” or simplifying the language. The teacher is careful to use clear speech and to enunciate. This will help children later when it comes time to learn to write and spell.

In early childhood, language is taught through story time and circle time: songs, verses, rhymes and poems are all incorporated. It may look like play, but language skills are being developed daily.

Repetition

Because the same circle time sequence is repeated daily for 2-3 weeks at a time, children learn the songs and verses “by heart,” and will retain them for life.

Rudolf Steiner, founder of Waldorf education, stressed the importance of repetition when he developed the first Waldorf school in Germany in the 1920’s. Current brain research confirms that repetition aids a child’s brain development. The connections of billions of neural pathways in the brain are strengthened through repeated experiences.

Speaking

A visitor to a Waldorf kindergarten might notice the children are not being taught the ABC’s. They are not given worksheets, nor do they practice reading from books. But we Waldorf teachers know that language skills are being built through the repetition of stories, songs and verses. We are preparing children to read and write through the spoken word.

On the other hand, that same observer is likely to be impressed by the children’s precocious verbal abilities; their impressive vocabulary, and the number of poems and stories that they can recite by heart.

In addition to our work with speech, we work on building a child’s fine motor skills—through activities such drawing, finger knitting and sewing—to prepare children for the next stage of language development: writing.

Writing

It is during first grade in a Waldorf School when the alphabet is formally introduced, but in an imaginative, pictorial way. Think again of hieroglypics. Each letter of the alphabet is introduced as a symbol, representing an element from a story the children are told. For example, they might hear the story of a knight on a quest who had to cross mountains and a valley. The children will then draw a picture with the letter “M” forming the Mountains on either side of the “V” for Valley.

Blackboard Drawing by Allen Stovall

In this way, the child develops a living relationship with each letter and the written word. It is not dry and abstract. Writing is taught in a way that engages the child’s imagination.

After learning all the letters, the next step is to copy the teacher’s writing. Typically the children will recite a poem together until it is learned by heart.

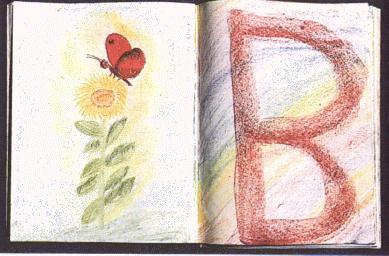

Then the teacher will write the poem on the board, and the children will copy it into their “main lesson books,” the books that children in a Waldorf school create themselves.

Because the children already know the poem and they have learned the alphabet, they will begin to make connections. “Oh, this must spell “brown bear” because both these words start with “B” and those are the first two words of the poem!”

Reading

The final step is learning to read, which generally starts in second grade and continues into third grade.

It is important to know that reading requires decoding skills that develop in children at varying ages. In Waldorf education we understand that learning to read will unfold naturally in its own time when a child is given the proper support.

Just as a normal, healthy child will learn to walk without our teaching her, and just as a child miraculously learns to speak her native language by the age of three without lessons, worksheets or a dictionary, so will a child naturally learn to read when she has a positive relationship with the spoken and written word.

Books

Yes, it is true that early readers and textbooks are generally not used in Waldorf education. Instead, the children are fed real literature starting in the earliest years.

Once students are fully reading, they turn to original source texts such as classic literature and biographies, and students will read many great books throughout their grade school years.

What they avoid are early readers of the “See Spot run” variety, and dry, lifeless textbooks.

My Children

It can be hard to trust that this system works, especially when your child’s public school peers are reading at 5, 6 or 7. But I offer you the example of my two sons.

My younger son Will taught himself to read in kindergarten; my older son Harper wasn’t fully reading until third grade. Yet, for each of them, once the decoding skill was unlocked, they became voracious and insatiable readers, consuming piles of books for pleasure throughout their childhood. In high school, Harper scored in the 98th percentile for reading on the SAT.

The age at which they learned to read had no bearing on their lifetime love of reading. However, I believe that the way they were educated had everything to do with it.

Thinking again of my old friend, I wish I knew then what I know now, and could have corrected her misguided perception. Perhaps her children, like mine, might have reaped the bounteous fruits of Waldorf education.

Are your children in a Waldorf school? Are you a Waldorf homeschooler? Considering Waldorf education? Is your child reading yet? Are you concerned about late reading? I’d love to hear your thoughts and comments!

![]()